TRUDI VAN DER ELSEN is a contemporary multi-media artist, based in Ireland since 2004. Her practice includes painting, drawing, installation work, performance and lens-based media. She exhibits regularly both nationally and internationally.

Recent exhibitions have included;

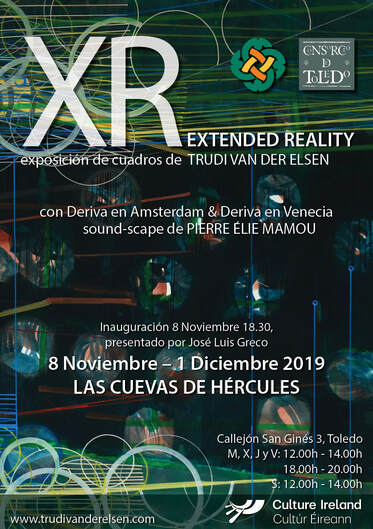

Beyond Brushstrokes: Between Matter and Memory, curated by Sara Foust, Courthouse Gallery, Ennistymon, 2024, ECHO, solo exhibition at Walters, Dún Laoghaire, Dublin 2023, Estuary, solo exhibition at Custom House Gallery, Westport, Co Mayo 2023, Sionainn, solo exhibition, Limerick Museum 2023, OPERE, Weber & Weber Gallery, Turin, Italy, 2023, Breaking Borders, Curated by Valeria Ceregini, Luan Gallery, Athlone & GOMA, Waterford, IRL (2022), Artists from Ireland, online exhibition, Sasse Art Museum, Los Angeles, USA (2021), Fragmented Perception, solo exhibition, Weber & Weber Gallery, Turin, Italy (2021), RHA Annual, Dublin, Ireland (2020), Notes From A Digital Sea, solo exhibition, BCA Gallery, Ireland (2020). XR-Extended Reality, solo exhibition,Toledo, Spain (2019), inclusion in the National Self Portrait Collection at The Bourne Vincent, Ireland (2018), Songlines, solo exhibition, Punt WG, Amsterdam (2012), selection for the RUA Belfast Annual (2015 &2017).

Her work has been supported by the Arts Councils of Holland and Ireland, as well as Culture Ireland and Clare County Council. Her work is in private and public collections internationally, and in Ireland collected by the OPW and Clare County Council. In addition to her work as an artist she has also been the curator of the Courthouse Gallery, Ennistymon from (2009-2016).

Recent exhibitions have included;

Beyond Brushstrokes: Between Matter and Memory, curated by Sara Foust, Courthouse Gallery, Ennistymon, 2024, ECHO, solo exhibition at Walters, Dún Laoghaire, Dublin 2023, Estuary, solo exhibition at Custom House Gallery, Westport, Co Mayo 2023, Sionainn, solo exhibition, Limerick Museum 2023, OPERE, Weber & Weber Gallery, Turin, Italy, 2023, Breaking Borders, Curated by Valeria Ceregini, Luan Gallery, Athlone & GOMA, Waterford, IRL (2022), Artists from Ireland, online exhibition, Sasse Art Museum, Los Angeles, USA (2021), Fragmented Perception, solo exhibition, Weber & Weber Gallery, Turin, Italy (2021), RHA Annual, Dublin, Ireland (2020), Notes From A Digital Sea, solo exhibition, BCA Gallery, Ireland (2020). XR-Extended Reality, solo exhibition,Toledo, Spain (2019), inclusion in the National Self Portrait Collection at The Bourne Vincent, Ireland (2018), Songlines, solo exhibition, Punt WG, Amsterdam (2012), selection for the RUA Belfast Annual (2015 &2017).

Her work has been supported by the Arts Councils of Holland and Ireland, as well as Culture Ireland and Clare County Council. Her work is in private and public collections internationally, and in Ireland collected by the OPW and Clare County Council. In addition to her work as an artist she has also been the curator of the Courthouse Gallery, Ennistymon from (2009-2016).

STATEMENT

“The landscape mirrors itself in me and I mirror its consciousness“ Cezanne

“The expression is something that in the medium itself lives, not imposed from outside, but in and through the medium itself is generated “Merleau Ponty.

“Intuition is nothing other than that which we understand as thought, but it is a superior form of thinking, an enlarged consciousness in which one realizes that man is free” Joseph Beuys.

The virtual network between computers has transformed our perception and experience of the world from the single historical ‘vanishing point’ to a multi-dimensional view. My work explores the potential of painting to express the unique quality of stillness and treatment of time in an ever-accelerating experience of hyper-linked reality.

My paintings investigate and echo this multi-dimensional view of perception, not as a representation but rather as a distillation of an essence, a re-creation and transformation; a new way to make visible the inner and the outer layers of perception, simultaneously.

My practice is influenced and excited by the natural environment, the land and landscape surrounding my studio on the Shannon Estuary in South West Clare. In particular the River Shannon, the mythology of the river goddess Sionainn and Connla’s Well. These mythologies resonate with me and inspire me to extend myself, to be open in the process of creative expression.

I work intuitively, a working process that echoes a natural response to materials, to feelings, to environment, or subject, with all senses involved. A slow process of pulling and pushing, creating and deleting, resulting in a multi-layered image, where brushed organic forms and pen marks compliment or vie for position within spaces, within layers. I often work on a large scale to augment an immersive, embodied experience.

The river transports me to another world, back to the ancient source and back to my own source, before time, an undefined place, the place of not-knowing, the place of nothingness, a pause, followed by a continuation, filling up endlessly – energising.

“Sionainn, the mythological Goddess of the river, broke free from the strangle hold of society and travelled deep beneath the ocean to Connla’s Well, a supernatural spring that could assist her on the journey to knowledge or enlightenment. She managed to imbibe some of the frothy bubbles of wisdom and her gift of enlightenment and creativity was granted. When she reached the point of possible freedom the well rose up and drowned her.

Sionainn is connected to the Otherworld, where time is not linear but cyclical and she is deeply entwined with the fertility of the land, the circularity of the seasons and cycles of the moon and the tides.

Connla’s Well, the well that never dries up, represents imagination, vision and creativity”

- Manchán Magan in Listen to the Land Speak.

“The landscape mirrors itself in me and I mirror its consciousness“ Cezanne

“The expression is something that in the medium itself lives, not imposed from outside, but in and through the medium itself is generated “Merleau Ponty.

“Intuition is nothing other than that which we understand as thought, but it is a superior form of thinking, an enlarged consciousness in which one realizes that man is free” Joseph Beuys.

The virtual network between computers has transformed our perception and experience of the world from the single historical ‘vanishing point’ to a multi-dimensional view. My work explores the potential of painting to express the unique quality of stillness and treatment of time in an ever-accelerating experience of hyper-linked reality.

My paintings investigate and echo this multi-dimensional view of perception, not as a representation but rather as a distillation of an essence, a re-creation and transformation; a new way to make visible the inner and the outer layers of perception, simultaneously.

My practice is influenced and excited by the natural environment, the land and landscape surrounding my studio on the Shannon Estuary in South West Clare. In particular the River Shannon, the mythology of the river goddess Sionainn and Connla’s Well. These mythologies resonate with me and inspire me to extend myself, to be open in the process of creative expression.

I work intuitively, a working process that echoes a natural response to materials, to feelings, to environment, or subject, with all senses involved. A slow process of pulling and pushing, creating and deleting, resulting in a multi-layered image, where brushed organic forms and pen marks compliment or vie for position within spaces, within layers. I often work on a large scale to augment an immersive, embodied experience.

The river transports me to another world, back to the ancient source and back to my own source, before time, an undefined place, the place of not-knowing, the place of nothingness, a pause, followed by a continuation, filling up endlessly – energising.

“Sionainn, the mythological Goddess of the river, broke free from the strangle hold of society and travelled deep beneath the ocean to Connla’s Well, a supernatural spring that could assist her on the journey to knowledge or enlightenment. She managed to imbibe some of the frothy bubbles of wisdom and her gift of enlightenment and creativity was granted. When she reached the point of possible freedom the well rose up and drowned her.

Sionainn is connected to the Otherworld, where time is not linear but cyclical and she is deeply entwined with the fertility of the land, the circularity of the seasons and cycles of the moon and the tides.

Connla’s Well, the well that never dries up, represents imagination, vision and creativity”

- Manchán Magan in Listen to the Land Speak.

Text in Catalogue Frequencies of Light, by Peter van Lier, poet and writer of essays on poetry, philosophy and art (NL)

Lenses

Since a number of years, Trudi van der Elsen has rediscovered painting and created new works in an idiom all of her own. Before, she had made a name in art mainly as a performance artist. On evocative photos and in films she was the magical centre of a staged action. I remember a consecutive series of photos in which she falls into a moor, going under; the suggestion is created that she won’t resurface. The series refers indirectly to the hidden bog bodies that were found here and there.

Van der Elsen has always been fascinated by submersion in darkness. Not so long ago, she created photos made using a pinhole camera. Such a device consists of little more than a hole in a cylinder where light can penetrate to a light-sensitive rear panel. This way, too, she demonstrates how a reality can exist in pitch darkness.

This fascination reminds me of Alice in Wonderland, the more than famous children’s book by Lewis Carroll. Alice crawls into a rabbit hole, following a white rabbit, and falls deeper and deeper into darkness.

On the bottom of the hole she lands in an illuminated space, where she opens a small door offering a view of the most beautiful garden she ever saw. ‘Oh, how I wish I could shut up like a telescope’, Alice ponders; downsized, she would be able to enter that garden and wander around in it with a sharpened gaze.

Trudi van der Elsen’s recent paintings remind me of this view. The images may be abstract and digitally inspired, but in their formal language, lines and colour just as tempting and beautiful as Alice’s dream garden.

From a post-modern perspective such an artificial world, in which all ties with concrete reality seem to be broken, may scare off. The rabbit hole into which Alice disappears can be compared to the black holes in space into which all forms and all light are absorbed, but through this dark passage she enters into another world.

Trudi van der Elsen also shows us an unknown world in her paintings, but just like with Alice she makes no distinction between normal reality and another reality. Living a secluded life on one of the banks of the river Shannon in Ireland, but unmistakably with a computer within reach, she ponders: ‘Thanks to cyberspace we sit in our chair and communicate with the world’. If there are books of post-modern philosophers on her bedside table, in which the contact with reality is increasingly broken, Alice in Wonderland will be on top of the pile as the ideal read before falling asleep. In this book an intense bond with the world is restored through a child’s gaze of wonderment.

A philosophical book for which there will certainly be room on her bedside table is Spinoza’s Ethics. Van der Elsen paintings immediately offer a view of the wonderous world of a digital universe, the twenty-first century version of Spinoza’s divine world, which does not transcend nature around and inside us, but is directly linked to it. Spinoza cut lenses to earn a living; the circles in Van der Elsen’s paintings also look like lenses zooming in on the world. And it won’t surprise Van der Elsen that Alice wants to enter the wonderful garden under the ground as a retractable telescope. She is Alice and Spinoza all in one. Digital dream images and views of her garden on the river are mixed naturally on her canvases into her own, contemporary wonderland.

Peter van Lier

Fragmented Perception curated by Valeria Ceregini https://valeriaceregini.com

part of the trilogy Painting through its poetical emotions #3 at Weber & Weber Galleria, Turin, Italy, 14 Sep - 30 Oct 2021.

The visual and performative artist Trudi van der Elsen introduces in this new group of works a fragmentary perception of reality – hence the title Fragmented perception– specifically, two worldviews: one local and one global. Through the abstract painting, van der Elsen explores both the visual and digital world matching her real and virtual experiences in her paintings through the use of multiple layers of colours and marks laid on progressively on the canvas to capture on the surface of her paintings the myriad movements of the virtual world. Thus, the surface becomes the place of various vanishing points generated by the authentic artist’s experience of the world.

Time plays a fundamental role in van der Elsen’s pictorial practice, it is released as a form of energy in every phase of her work, from conception to realisation. Body gestures and soul movements are aimed to let her creativity flow freely on canvas placing herself in an intuitive time. Like jazz music, she is trusting in the flow of improvisation where all her experiences come through in painting.

Everything is in constant movement, a flow of gestures and colours that indicate both the artist’s physical movements and the passages of time. Van der Elsen affirms, indeed, that through painting she places herself into the time flow, a performative time, of action, of “being in time” hic et nunc.

During her creative and intuitive process, the marks on canvases follow one another her thoughts and emotions, and through together in the artist’s mind until they find their place on the canvas creating the right composition of the final abstract image. Therefore, it becomes a captured instant of that time that reflects exactly the harmonic intensity, the artistic and poetic climax.

The research process that led Trudi van der Elsen to the realisation of these pieces is an intuitive improvisation proceeding by organic brushstrokes and pen marks intertwining and contrasting themselves among several pictorial stages and levels. Furthermore, van der Elsen's oeuvre involving her whole body, especially in the large canvases is evident the embodiment of the painter. At the same time, this improvisation of movements are inviting the bystander to get lost in these new illusory visual mind spaces escaping from reality.

In Trudi van der Elsen’s painting memory, observation, intuition, knowledge, technical ability, technology and history come together in a unique and unprecedented image where the phases of realisation – often linked to personal visual experiences such as the enchanting estuary of the River Shannon in Ireland – they are blended to fade and then giving life to a new space of imagination. These “landscapes” become the landscapes of mind that however take on concreteness and truthfulness in their abstraction .

Valeria Ceregini

|

XR - Extended Reality - Las Cuevas de Hércules, Toledo - November, 2019.

Having spent many years engaging directly with the land and seascapes of Ireland where van der Elsen lives, her work has evolved through the slow, concentrated focus of painting. The artist describes herself as being caught between the local and global world view. The first is real and transient, while the latter is virtual, synthetic and petrifying. These recent works utilize digitization as a new source of abstraction. The speed and the flickering of the virtual world, creates a level of alienation and de-coupling. The slowness of the act of painting serves to ground these hyper-movements with multiple vanishing points in the image representing our fragmented experiences of ourselves and our world. Although the finished work is a still image, it does not mean that the image is still. The energy and motion concentrated within is always present, just waiting to be activated by the perceiver. The artist paints on a large scale,intuitively producing works that create an immersive and embodied experience for the viewer. In Toledo, the experience will be enhanced by the sound-scape of Pierre Élie Mamou. The collaboration between the artist and composer centers on these shared ideas and opens another shift in engaging with their work. For this exhibition Mamou contributes Deriva en Venecia and Deriva en Amsterdam. ‘Art has to be experimental and springs from the experience of the artist and is continuously changing’, according to the Dutch artist Constant in his 1948 manifesto. ‘Deriva en Amsterdam’ (1981) Mamou: was realized in collaboration by Constant. consorciotoledo.com/mcomunicacion/index.asp |

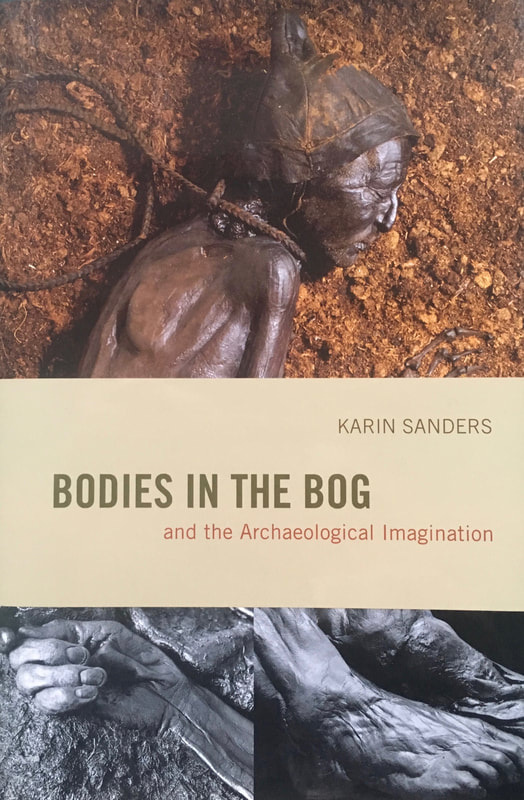

2009 Bodies In The Bog and the Archaelogical Imagination written by Karin Sanders, professor of Scandinavian Studies at the University of California, Berkely (University of Chicago Press)

Nostalgic Overlay: Trudi van der Elsen

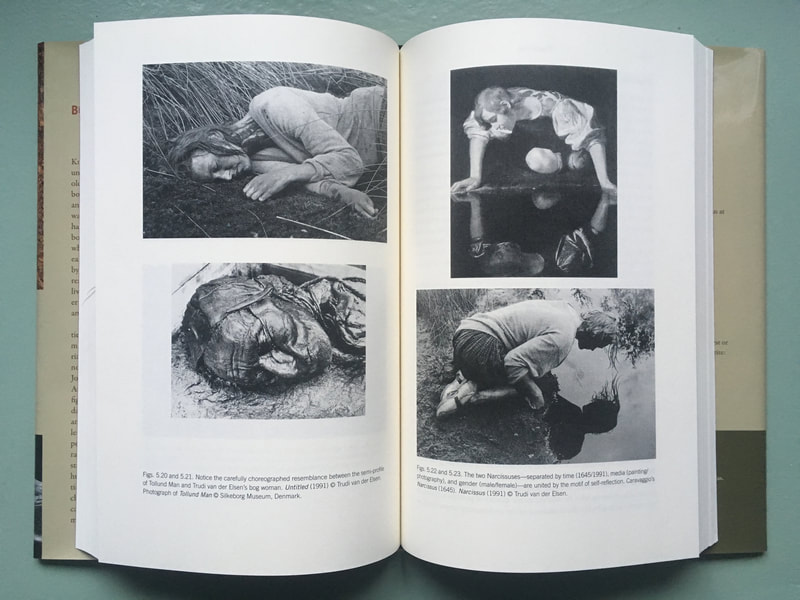

Self-display—or self-archaeologication—is even more pronounced in a photographic bog series by the Dutch artist Trudi van der Elsen. In a cycle of black-and-white still-shots which resemble freeze frames of an interrupted motion film, we see Tollund Man in the shape of a woman and witness how he (as a she) gradually walks into the bog, submerges and finally rests in the natal position of Tollund Man. Van der Elsen deliberately draws on the intimate analogy between archaeology and art photography and articulates a moment of shared time between the contemporary subject (here a woman) and the prehistoric object.[1] Her photographs take the structure of a visual story plucked as “quotations” from Glob’s account and as echoes of the photographic illustrations by Lennart Larsson. In this iconographical mimicry van der Elsen shows how a woman walks as if mesmerized into the bog lake and finally assumes the position in which Tollund Man was found.

If human sacrifice is the key to understanding the bodies in the bogs, the artist here gives us a photo-performance in which the sacrifice is re-staged as nostalgic self-sacrifice. In one photograph the woman’s face is actually depicted as if grafted directly onto that of Tollund Man’s as he is seen in Larsson’s photograph.

By mimicking the ancient face, which in the words of Glob is the best preserved “to have survived from antiquity in any part of the world” and on which “majesty and gentleness still stamp his features as they did when he was alive” van der Elsen changes the archaeological narrative into a subjective vision, evoking a sense of “mythography” to borrow a phrase from Mieke Bal.[2] That is, Van der Elsen’s archaeological-artistic mimicry is wrapped up in a coding of identity vis-à-vis alterity, as a performance of actuality, a strangely romanticized challenge for the modern subject. On the one hand there is an urgent sense of identification; on the other hand the play with quotations is both ironic and melodramatically self-conscious. Interestingly, van der Elsen not only quotes from Lennart Larson’s photograph of Tollund Man but also from Carravagio’s painting Narcissus. In a photograph, a woman is seen on her knees bending forward over a bog-lake as a mirror, like the one we see in Carravagio’s painting. In her work on Quoting Caravaggio, Mieke Bal offers a comment that could be applied to van der Elsen’s bog-mirror (although Bal’s book does not include van der Elsen’s work) when she says that “unlike the bodily skin, the mirroring surface touches visually, not physically. This does not make the act of seeing any less ‘touchy,’ sensitive, or formative to the subject. Only a semiotics focused on the production of meaning in coevalness can theorize the structural similarity between touching and seeing that is important here. For seeing is a semiotically informed act of indexicality, of reaching into space.”[3]

As a result, Trudi van der Elsen’s overlay of Glob’s archaeological photo-text transforms the 2000-year-old bog body from a materialization of a national-cultural to a personal memory. In her photo-series the bog-man-as-woman morphs into nostalgic artistic manifestations and remind us that nostalgia, as Svetlana Boym has argued, is about “repetition of the unrepeatable” and as such can become a way to overcome trauma. By walking back into the bog, back to a place of origin and by repeating the traumatic event, trauma can become nostalgia.

[1] Hal Foster would no doubt call it an example of over-identification; see The Return of the Real: The Avant-garde at the End of the Century (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1996), 203.

[2] P. V Glob, The Bog People; Iron Age Man Preserved (Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press, 1969), 31.

[3] Mieke Bal, Quoting Caravaggio: Contemporary Art, Preposterous History (Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press, 1999), 233.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Exhibition : BOG, Courthouse Gallery, Ennistymon (IRL) - 2010

Embracing the bogman. - by Fiona Woods

In Ireland ‘bogman’ is a pejorative term used specifically in relation to rural people, conjuring up a sense of someone who is ‘too close’ to the land. It implies an inferior level of civilisation, a lack of culture. As a term of abuse, it captures the attempts of the ‘modern’ world to distance itself from the pre-industrial world, and the resulting tension of the human as product of both nature and culture.

From a post-modern vantage point, we can see the ‘triumph’ of culture over nature as a hollow victory. The values inherent in the Modernist rejection of nature blinded us to the consequences of our actions, which are just now becoming visible. All accepted notions about progress and value demand an urgent reworking: art has an important role to play in this, primarily by challenging us to review all clichés about what constitutes nature and/or culture and to reconsider the false dichotomy between the two.

Bog by Trudi van der Elsen is a body of work that locates itself in this uncertain place, in this questioning of the division of nature and culture. It draws largely on a series of performative works carried out by the artist along a geological line of boglands from Belgium to the Netherlands to Denmark, and is presented to us as a series of iconographic photo-images together with some paintings and a sculptural installation. It depicts a kind of descent into the supposed underworld of nature, where all is inverted and the bogman is revealed as master of a complex, symbolic realm.

The performative aspect of Bog began with a work entitled The Fall (1991), a series of six B/W photographs tracing the fall of a woman into the dense murky waters of a bog pool. Each image reads as a frozen moment, charged with the motion that must inevitably follow. At the time of making these works van der Elsen was conscious of the mythic undertones rippling through them, so it is no accident that Fall is the starting point for what reads initially as a ‘descent into nature’. No single mythic tradition is evoked here, but the multiple strands and traditions that have woven their way into Western European consciousness – Judaeo-Christian, Ancient Greek, Nordic, and pagan.

Yet it is undoubtedly the shamanic tradition, and the female shamanic tradition in particular, that is most to the fore here. The artist-shaman (who, since Joseph Beuys, lurks always at the edges of contemporary art) becomes a proxy, enduring trials beyond the capacity of most people, to bring back a message from the other side of experience. In Bog the journeying figure morphs from female to male, from dark to light, from innocent to malevolent. Her props and costumes are heavy, traditional, and unflattering, and more than once the works evokes the shadow world of medieval fairytales in all their puzzling and sometimes gruesome detail.

The overall effect is of a series of film-stills, intensely iconic images that are both remarkably still and trembling with the weight of multiple readings. The presence of a traditional rike of turf in the centre of the gallery space has an important grounding effect, drawing the charge of the images without neutralising them. The work seems to capture a shift from thinking about nature as something out there, on the other side of a car window or television screen, to an understanding that what is happening around us is also what is happening to us, for good and for bad.

The poster for the exhibition showed one of the works in which the artist is lying almost face down in the bog, smeared with mud. A woman working in the local print shop where the posters were produced said that she thought the image was degrading to women. Outside of the safer context of the gallery the work was rawer, more threatening, less easily read and consumed.

The performative works from Bog have a tremendous power that derives from the artist’s evident willingness to place herself outside the limits of her own control. Whether the wildness of that experience is overly tamed once inside the white cube gallery space is a question that remains for me, and one that I would be interested to see this artist explore further.

Fiona Woods

http://www.fionawoods.net/

April 2010

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

LURE OF THE BOG

(For Trudi van der Elsen)

Here, within this bog, today

Both lost and found, at once, decay.

Once young, now pre-folklyric days

Not centuries but millennia away

For here I’ve seen the Bog-man’s grave

From Jutland, here his aura safe

From rotting roots and mossy moors,

From hateful hunters and their whoors,

To haunt his own gravediggers grim,

To torture those who tortured him,

Not for redress but equipoise:

Their silent screams, Beelzebub’s cries!

Elemental wrongs from ancient time

Still seething, post suburban slime;

Human suffering’s dark domain

Where crime’s contaminations reign

O’er much of what should offer joy

As once it did for me, a boy

Who roamed such bog-lands without care.

Now Fire and Water, Earth and Air

Unsettled, ill-at-ease, all tease

My bones to lay ’neath rotten leaves!

As Heaney’s words of beauty claim

The Tollund Man’s age-old refrain,

Van der Elsen shows the pain

Of long lost bog-land people slain:

We dig the turf, we strip the moor,

Still the bog’s lure “Return once more”.

Written by Ron Kavana to celebrate the Bog exhibition, March 2010

Nostalgic Overlay: Trudi van der Elsen

Self-display—or self-archaeologication—is even more pronounced in a photographic bog series by the Dutch artist Trudi van der Elsen. In a cycle of black-and-white still-shots which resemble freeze frames of an interrupted motion film, we see Tollund Man in the shape of a woman and witness how he (as a she) gradually walks into the bog, submerges and finally rests in the natal position of Tollund Man. Van der Elsen deliberately draws on the intimate analogy between archaeology and art photography and articulates a moment of shared time between the contemporary subject (here a woman) and the prehistoric object.[1] Her photographs take the structure of a visual story plucked as “quotations” from Glob’s account and as echoes of the photographic illustrations by Lennart Larsson. In this iconographical mimicry van der Elsen shows how a woman walks as if mesmerized into the bog lake and finally assumes the position in which Tollund Man was found.

If human sacrifice is the key to understanding the bodies in the bogs, the artist here gives us a photo-performance in which the sacrifice is re-staged as nostalgic self-sacrifice. In one photograph the woman’s face is actually depicted as if grafted directly onto that of Tollund Man’s as he is seen in Larsson’s photograph.

By mimicking the ancient face, which in the words of Glob is the best preserved “to have survived from antiquity in any part of the world” and on which “majesty and gentleness still stamp his features as they did when he was alive” van der Elsen changes the archaeological narrative into a subjective vision, evoking a sense of “mythography” to borrow a phrase from Mieke Bal.[2] That is, Van der Elsen’s archaeological-artistic mimicry is wrapped up in a coding of identity vis-à-vis alterity, as a performance of actuality, a strangely romanticized challenge for the modern subject. On the one hand there is an urgent sense of identification; on the other hand the play with quotations is both ironic and melodramatically self-conscious. Interestingly, van der Elsen not only quotes from Lennart Larson’s photograph of Tollund Man but also from Carravagio’s painting Narcissus. In a photograph, a woman is seen on her knees bending forward over a bog-lake as a mirror, like the one we see in Carravagio’s painting. In her work on Quoting Caravaggio, Mieke Bal offers a comment that could be applied to van der Elsen’s bog-mirror (although Bal’s book does not include van der Elsen’s work) when she says that “unlike the bodily skin, the mirroring surface touches visually, not physically. This does not make the act of seeing any less ‘touchy,’ sensitive, or formative to the subject. Only a semiotics focused on the production of meaning in coevalness can theorize the structural similarity between touching and seeing that is important here. For seeing is a semiotically informed act of indexicality, of reaching into space.”[3]

As a result, Trudi van der Elsen’s overlay of Glob’s archaeological photo-text transforms the 2000-year-old bog body from a materialization of a national-cultural to a personal memory. In her photo-series the bog-man-as-woman morphs into nostalgic artistic manifestations and remind us that nostalgia, as Svetlana Boym has argued, is about “repetition of the unrepeatable” and as such can become a way to overcome trauma. By walking back into the bog, back to a place of origin and by repeating the traumatic event, trauma can become nostalgia.

[1] Hal Foster would no doubt call it an example of over-identification; see The Return of the Real: The Avant-garde at the End of the Century (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1996), 203.

[2] P. V Glob, The Bog People; Iron Age Man Preserved (Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press, 1969), 31.

[3] Mieke Bal, Quoting Caravaggio: Contemporary Art, Preposterous History (Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press, 1999), 233.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Exhibition : BOG, Courthouse Gallery, Ennistymon (IRL) - 2010

Embracing the bogman. - by Fiona Woods

In Ireland ‘bogman’ is a pejorative term used specifically in relation to rural people, conjuring up a sense of someone who is ‘too close’ to the land. It implies an inferior level of civilisation, a lack of culture. As a term of abuse, it captures the attempts of the ‘modern’ world to distance itself from the pre-industrial world, and the resulting tension of the human as product of both nature and culture.

From a post-modern vantage point, we can see the ‘triumph’ of culture over nature as a hollow victory. The values inherent in the Modernist rejection of nature blinded us to the consequences of our actions, which are just now becoming visible. All accepted notions about progress and value demand an urgent reworking: art has an important role to play in this, primarily by challenging us to review all clichés about what constitutes nature and/or culture and to reconsider the false dichotomy between the two.

Bog by Trudi van der Elsen is a body of work that locates itself in this uncertain place, in this questioning of the division of nature and culture. It draws largely on a series of performative works carried out by the artist along a geological line of boglands from Belgium to the Netherlands to Denmark, and is presented to us as a series of iconographic photo-images together with some paintings and a sculptural installation. It depicts a kind of descent into the supposed underworld of nature, where all is inverted and the bogman is revealed as master of a complex, symbolic realm.

The performative aspect of Bog began with a work entitled The Fall (1991), a series of six B/W photographs tracing the fall of a woman into the dense murky waters of a bog pool. Each image reads as a frozen moment, charged with the motion that must inevitably follow. At the time of making these works van der Elsen was conscious of the mythic undertones rippling through them, so it is no accident that Fall is the starting point for what reads initially as a ‘descent into nature’. No single mythic tradition is evoked here, but the multiple strands and traditions that have woven their way into Western European consciousness – Judaeo-Christian, Ancient Greek, Nordic, and pagan.

Yet it is undoubtedly the shamanic tradition, and the female shamanic tradition in particular, that is most to the fore here. The artist-shaman (who, since Joseph Beuys, lurks always at the edges of contemporary art) becomes a proxy, enduring trials beyond the capacity of most people, to bring back a message from the other side of experience. In Bog the journeying figure morphs from female to male, from dark to light, from innocent to malevolent. Her props and costumes are heavy, traditional, and unflattering, and more than once the works evokes the shadow world of medieval fairytales in all their puzzling and sometimes gruesome detail.

The overall effect is of a series of film-stills, intensely iconic images that are both remarkably still and trembling with the weight of multiple readings. The presence of a traditional rike of turf in the centre of the gallery space has an important grounding effect, drawing the charge of the images without neutralising them. The work seems to capture a shift from thinking about nature as something out there, on the other side of a car window or television screen, to an understanding that what is happening around us is also what is happening to us, for good and for bad.

The poster for the exhibition showed one of the works in which the artist is lying almost face down in the bog, smeared with mud. A woman working in the local print shop where the posters were produced said that she thought the image was degrading to women. Outside of the safer context of the gallery the work was rawer, more threatening, less easily read and consumed.

The performative works from Bog have a tremendous power that derives from the artist’s evident willingness to place herself outside the limits of her own control. Whether the wildness of that experience is overly tamed once inside the white cube gallery space is a question that remains for me, and one that I would be interested to see this artist explore further.

Fiona Woods

http://www.fionawoods.net/

April 2010

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

LURE OF THE BOG

(For Trudi van der Elsen)

Here, within this bog, today

Both lost and found, at once, decay.

Once young, now pre-folklyric days

Not centuries but millennia away

For here I’ve seen the Bog-man’s grave

From Jutland, here his aura safe

From rotting roots and mossy moors,

From hateful hunters and their whoors,

To haunt his own gravediggers grim,

To torture those who tortured him,

Not for redress but equipoise:

Their silent screams, Beelzebub’s cries!

Elemental wrongs from ancient time

Still seething, post suburban slime;

Human suffering’s dark domain

Where crime’s contaminations reign

O’er much of what should offer joy

As once it did for me, a boy

Who roamed such bog-lands without care.

Now Fire and Water, Earth and Air

Unsettled, ill-at-ease, all tease

My bones to lay ’neath rotten leaves!

As Heaney’s words of beauty claim

The Tollund Man’s age-old refrain,

Van der Elsen shows the pain

Of long lost bog-land people slain:

We dig the turf, we strip the moor,

Still the bog’s lure “Return once more”.

Written by Ron Kavana to celebrate the Bog exhibition, March 2010

Copyright Trudi van der Elsen